The massively multiplayer role-playing game EVE Online, and its developer CCP, have long had a unique (and sometimes complicated) relationship with the real world. The sci-fi space exploration, combat and economics game has been studied by real world economists; its artwork is featured at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA); and the game recently launched an ambitious undertaking called Project Discovery, where players can help scientists from the University of Reykjavik and the University of Geneva identify possible exoplanets in the far reaches of space.

Those projects only tell half the story, as EVE Online has also reached into entertainment in addition to art and science. For example, it has an in-house music band called The Permaband, which released two free music tracks on the game Rock Band for players to enjoy. Furthermore, there are art, history and comic books based on the EVE universe, with the most recent being The Frigates of EVE.

Speaking with AListDaily, Torfi Frans Olafsson, senior director of business development for North America at CCP, described Frigates as a “super-nerdy detailed lore book about what happens inside the EVE spaceships.” It is also co-authored by Charles White—best known in EVE Online circles as the “Space Pope” due to the character he plays at fan events—who actually works at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The book is a prime example of how the game and its community are intricately woven together, and how the stories of EVE are the stories of its players. It’s something that CCP keeps in mind as it expands its world through transmedia partnerships to grow interest in EVE beyond the player base.

Olafsson likens CCP’s approach to its IP to licensed Lego products, where the company presents them as one thing, but users and communities reshape them into something else. He emphasizes the importance of giving players tools to generate their own narratives, stating that the creativity is just as important as the lore that inspires it.

For perspective, some of the most prominent stories to come out of EVE include a mercenary group that spent real years infiltrating the ranks of an in-game organization to destroy all its ships and wealth from within. It wasn’t anything personal, just business. That’s on top of the multitude of wars and conflicts, one of which started because someone accidentally clicked on the wrong button.

However, it’s important to note that players’ stories are not the same as fan fiction. Although Olafsson believes fan fiction is an important factor, he believes that it looks inward toward fan communities. CCP’s goal is to amplify EVE Online’s stories to bring them out to the world.

Olafsson then went into detail about how CCP learned to capitalize on an IP with a narrative that the company doesn’t necessarily control.

What are some of the transmedia opportunities has CCP taken advantage of with EVE Online?

Like with many IPs, we generated the backstory and other aspects as a means to explain why you would want to fly ships into space. Now it has become a world and universe of its own in which millions of people thrive and it has its own collective history. Capitalizing on that, we’ve made some strides with the IP, with the first being simple things like novels set in the universe. But as the game progressed, we discovered that the thing both our players and the audience outside the game connected with was the true narrative—the stories of our players’ activities. The fantastic heists, the corporate espionage, and the great wars where tens of thousands of people went to war for months and even years. That has been a very strong focus of our IP development.

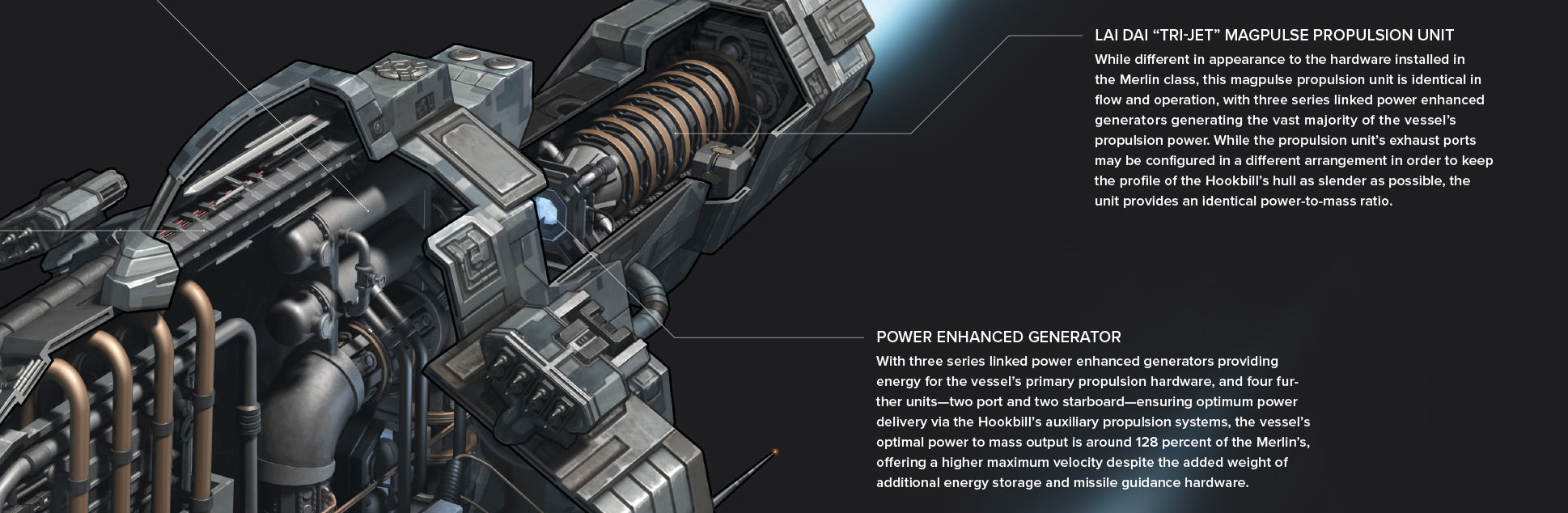

For example, we worked with Andrew Groen to publish a history book on the EVE empires (Empires of EVE: A History of the Great Wars of EVE Online), which sold very well on Kickstarter. We crowdsourced a number of stories from our players and published a comic book in partnership with Dark Horse Comics (EVE: True Stories) based on them. We’re also pushing out books with ship cutaways (The Frigates of EVE Online). We have also been working for a number of years on a television series that’s inspired and based on true stories. That series is in development, so we haven’t seen it on screen yet, but we’ve been approached by various media companies that are interested in telling stories that actually happened 20,000 years in the future.

Do you think the television series would be animated or live-action?

The way we’re looking at it is live-action. But like I said, it’s still in development. We’ve partnered with great people on it including Ridley Scott’s production company, Scott Free, and we’ve been exploring options while talking to potential studios. For some of the more established companies, the idea of creating a science fiction story that’s true is weird and they can’t fully grasp the concept. Perhaps they still think of games as single-player experiences and can’t appreciate the community and the value of a story that’s been crafted through the efforts and actions hundreds of thousands of people. But some of them certainly get it.

Does relying on true stories limit the amount of content you can create? Do you eventually plan on creating fictional stories based in the EVE universe?

That was actually the original idea. When we were planning the game, we didn’t account for the community. We thought of it more as a one-way street, where we were like gods who dictated what the world was and what happened in it. But over the course of 14 years, what happened midway was that the players stole the narrative. Their actions became more interesting than our own stories and there was an incident that involved actual activism and rioting within the game.

Players gained command of where the game was headed through the Council of Stellar Management (a democratically player-elected body), through the alliances, and infiltration into our ranks by becoming game designers and senior figures within the company. We as the original developers have, in a way, lost control of the narrative and had to yield to the great democratic body of the players. Today, we are more of custodians of the EVE Online universe than we are the gods of it. That’s a strange thing to come to terms with because we had to rewire our heads as that transition was happening. It was like maturing a relationship where we accepted our limitations and saw the power in each other.

How does CCP present content for transmedia partnerships when new stories are being created in real-time within the game, some spanning years?

We’re learning as we go along. I remember when we were doing the comic book with Dark Horse, I was trying to think of an example of where this had been done before to act as a template. I couldn’t find one. There’s no playbook for taking a narrative that’s been shaped by so many people and crafting it into something. At times, we thought we could do it with big data analysis and tracking people like we were the NSA or something. But in the end, it just comes down to good storytelling and journalism.

Andrew Groen spent a year interviewing close to 100 EVE players and recorded the history of EVE’s empires from 2003-2009, and now I think he’s working on a sequel. It needs a human touch. When you’re managing history or covering any major event, there is always a narrative perspective. There’s no way to be objective about it. You need a human to craft a story from all these disparate events and people. That is the only way to capture it, and often it’s best to bring in an outsider to analyze and record those stories. We at CCP are often too close to it to see the value in some events, or we may perceive something to be very important but is actually not so.

What is the target audience for these stories? Are they mainly for the fans or do they speak to sci-fi fans in general?

I think you can consider them concentric circles with EVE players being at the core of it. We are serving them by celebrating their history, but when we’ve looked at the press coverage of EVE over the past decade, the stories that have been featured in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, the BBC and Forbes have always been about our players. There have never been stories about our made-up universe. We found that there’s a great audience that’s interested in this world, even if they’re never going to play the game. That was also a pivot we made, realizing that this wasn’t just an acquisition tool for our product. This was a gateway into a universe, and we should find ways to amplify and monetize that interest without necessarily connecting it to game players.

Is it strange to be telling true stories about fictional game personas?

It is remarkably not strange. I think we’re fine with making that separation and distinction. One interesting area that applies to both gaming an internet culture, in general, is that the role of alter egos and anonymity has changed in the past few years. Fifteen or twenty years ago, it was more common for people to remain utterly anonymous and hidden behind an alias. But with social media and livestreaming, the person and character are both famous. The best example of that is Charles White, Space Pope, who has hundreds of thousands of online friends. Both his real-life and character personas are famous, and he mixes the two. He doesn’t hide behind his alter ego.

Do you see CCP creating its own media division someday?

It depends on specialization. As a company, we’ve gone through several iterations of defining ourselves. The sweet spot that we’ve landed at right now is focusing on what we are good at and partnering with those who are better at things we don’t know how to do. Building linear content is a craft that has evolved for over 100 years, and there are simply people who are way better at it than us. Our expertise is in generating computer games and generating online communities—we pride ourselves on doing that. There’s an inherent risk of losing focus [when you try to expand], so we’re partnering with experts as we venture into different spaces.