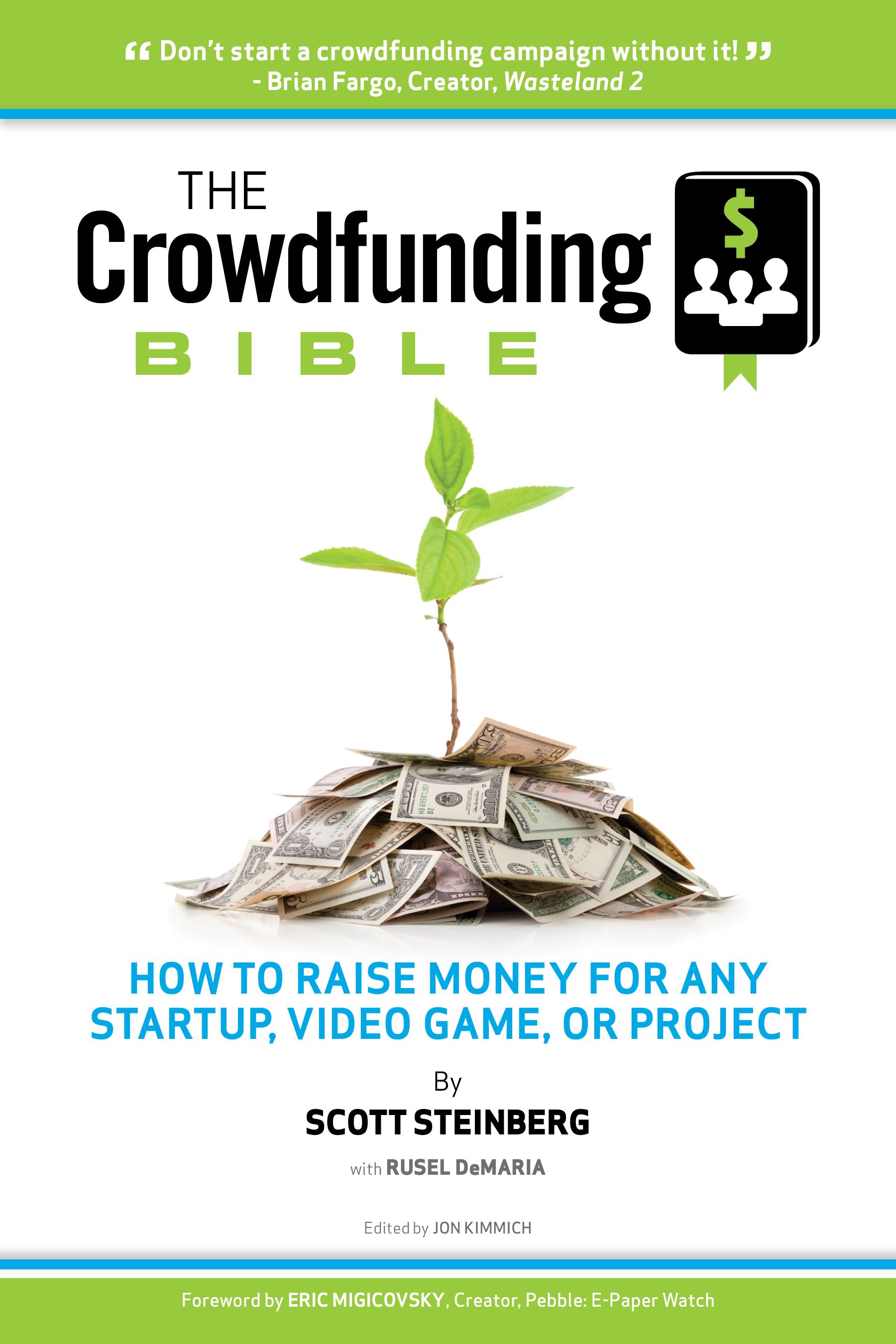

The recently published book The Crowdfunding Bible is a reminder of just how much of an impact digital publishing is having on the content business. Seemingly every content business. The timeliness of the book itself is indicative of it.

Authored by Scott Steinberg in collaboration with industry veterans Jon Kimmich and Russel DeMaria, it covers the surge in crowd funded game projects. It’s a topic that, at least to many in the game industry, reached the level of phenomenon just a few short months ago. It was when well-known game maker Tim Schafer turned to Kickstarter for his studio’s next big project, Double Fine Adventure. The campaign closed in March of this year in spectacular fashion, raising eight times more than it had hoped with over $3.3 million in funding.

That seemed to wake up the game industry to crowd sourcing as a viable way to raise capital for product development. At least one major publisher, EA, decided to throw its support behind it. And game players quickly caught on to yet another way indie developers empowered by digital distribution could serve their specific tastes. Three months later, there’s a comprehensive book on the topic, available digitally, and free to read. (Just go to www.crowdfundingguides.com.)

The [a]ilst daily had a chance to sit down with Scott Steinberg and Jon Kimmich to discuss their views on this transformative trend — yet another one — affecting the games business, and highlight major takeaways from their book for game makers, players and major publishers.

Tell me really briefly about the genesis of this book and how it brought the two of you, along with Russel DeMaria, together.

Scott Steinberg: Obviously crowd funding has been exploding in popularity, especially in the last several months with the success of games like Wasteland 2, Double Fine’s Adventure, of course other success like the Pebble E-Paper Watch and Shadowrun Returns returns. It was becoming obvious there was a growing need for more education and best practices surrounding this space. There is perilously little of it available for creators both in gaming and general consumer product spaces. Russel DeMaria and I had been kicking around the idea for a book. He specifically had just completed a successful Kickstarter project himself with [High Score 3rd Edition]. We saw this was a trend that was going to continue to explode in popularity. Jon and I got to talking as well and we said wouldn’t it be great if there were more resources.

What do you think is behind this seemingly sudden surge in interest and support for crowd funding?

Scott Steinberg: Media attention. The obvious thing is that the crowd funding movement has been growing and gaining in popularity over the past several years. It wasn’t until you had well known creators and designers like Tim Schafer who were bringing back popular properties that suddenly media attention catalyzed around these breakout success stories. Like any other industry when you start to have a number of breakout hits that you can latch on to, suddenly it consolidates industry attention.

Scott Steinberg

Scott Steinberg

Jon Kimmich: One of the things to keep in mind about crowd funding is that fundamentally the exercise that you’re engaging in is really an exercise in consumer marketing. It took people a while to figure out what this crowd funding thing is, how does it work and what type of skills and knowledge and tools can I take from other, more traditional things that have been done in marketing and utilize them and marshal them. The original inclination was less focus on commercial things and more indie. It’s evolved over time, and along with that the kind of project people can do with it has changed. As soon as it broke the million dollar barrier, I think that also started to get peoples’ attention, thinking wow I can actually get useful money out of this.

Scott Steinberg: Jon brings up a salient point in that the perceived limit that projects had to be under a hundred thousand dollars and often times in the tens of thousands of dollars was utterly shattered. Obviously the Pebble watch continued that tradition. What’s happened is even major players in the space are now looking at it as a viable alternative to VC.

What’s behind that shattered barrier, as you put it, to what people could suddenly raise through crowd funding?

Scott Steinberg: What I would say is that it’s effectively right moment, right time, where we reached that tipping point in terms of public attention, media awareness, willingness to take a plunge. And of course the tacit endorsement when you have a brand name celebrity, at least in the gaming industry, like Tim Schafer who is willing to turn to it very publicly as a potential source of funding, and not only succeeded but do it spectacularly. Suddenly you have a case study where thousands of developers out there who have their own following, as well as hopefuls looking to launch new IP into the market, waking up and saying, wait a minute, against all odds, here’s a creator making the types of games he loves to make who was suddenly able to defy the odds. Literally it’s the stuff Cinderella stories are made of.

Jon Kimmich: We did an interview with the design director of Obama’s 2008 campaign. When he was done, he decided he wanted to prepare this big, coffee table book. He told us the story of how he went to publisher A and publisher B and publisher C to try and sell his idea. The thing I remember from my interview with him was that after he went to all these publishers, he came to the conclusion that publishers suck! They wanted to take his vision for the book and turn it into this thing that he didn’t want. He talked to one of the Kickstarter guys, and he said why don’t you go and put it up on our site and see if you raise money. He did and it was wildly more successful than he thought it was going to be. I think he raised around $100,000.

Jon Kimmich

Jon Kimmich

Is there a pattern with what sort of game developers are turning to crowd sourced funding, and is it better suited to some products more than others?

Jon Kimmich: Initially there was this tendency for some folks to look at Kickstarter as this place where people funding projects were older, middle-aged men with disposable income who wanted to get back the nostalgia of games they played when they were young. And they had more money than common sense. I think that there are a number of projects we’ve seen funded successfully recently argue against that. You have something like The Banner Saga which raised three quarters of a million dollars. The folks behind that game aren’t anybody you’ve ever heard of, and they had no notoriety in games up until this point. Republique is also an original IP and it’s a new team. In terms of what kind of products make sense, I think it comes down to, number one, who’s the target audience you want to pitch the game to, and do you think there’s enough people out there to fund it at the level you’re trying to get funding. And then, how do you reach and target your message to them where they hang out and consume information about the kind of games they want to play, and what’s your plan to go out and deliver that message to them repeatedly so that over time they’ll make a decision that it’s something they want.

Scott Steinberg: The only thing I’d add to that is that the kind of games that most succeed are those that have either a strong existing fan following, that are tremendously unique, and of course that have wide cross-generational and cross-interest appeal that are also fairly reasonable when it comes to funding goals. Ultimately painting a picture in viewers’ minds as to just how unique the product is and what makes it so special and the marketplace, and why this is the right time to make it, and that you’re the right team to do the job.

Jon Kimmich: There was a campaign for a game called Takedown done by a guy named Christian Allen. They had no game to show. There was no game footage for their pitch. What they were really good at, and I think they were really smart about, was to define exactly what kind of game they were making, and if you played previous games of this sort then this was a game you would want to play because nobody’s making that kind of game right now. Their pitch was all about we’re going to make a game that’s very much like the original Rainbow Six, very tactical, thinking man’s shooter. There’s an audience out there for that kind of game that’s underserved. So they knew what their pitch was and how to target their messaging. They knew where their folks were hanging out on the internet, which web sites, and they raised a quarter of a million dollars. It wasn’t Double Fine level investment but they raised what they needed to make the game.

When it comes to raising awareness for a crowd funded project, what are the most important tactics or assets from a PR-marketing standpoint?

Scott Steinberg: I would argue that you are your greatest asset. Essentially you have to be a spokesperson and face for your movement. You have to have a plan in place before day one that incorporates a running spate and variety of activities that runs through the campaign’s duration. It would be a gross mistake to think that launch was the end for a specific campaign. Really what you need to do is have a game plan in place, have all of your assets in place prior to launch, know who you’re speaking to, who your audience is, how to best reach them, what vehicles and channels you have and what levers you can pull in terms of promotional assets and activities. And then realize that the goal is not to create a massive groundswell at a single point in time, but rather running buzz and constant conversation that keeps you top of mind. Ultimately it’s a mix of elements that are going to help you succeed. It’s not just social media, it’s not just press mentions. Any single activity may cause a spike in awareness and donation but at the end of the day you need to keep your ear to the ground. You need to be in constant contact with backers, you need to constantly be working the channels. Really not a day should pass by when outreach activities aren’t happening, whether you’re posting a bunch of updates or new screenshots or videos of the work in progress.

Jon Kimmich: An interesting thing I’ve heard from almost every team that I’ve talked to was they did not allocate enough of their time to all of this outreach activity. A lot of times it fell to the project lead or somebody who was pretty critical to getting the project done. That meant that when they’re doing outreach, they were getting pulled away from the project. You really need to have somebody who’s sole purpose during the campaign is to manage this outreach, and they should not be critical to the project.

In terms of assets, what’s most important to have, is it the fiction, is it a slick trailer, is it a prototype?

Jon Kimmich: The first thing I would say is that the bar is going to be raised over time. In my experience, generally what we see in terms of what people looked at first, is whatever happens to be on the top of the web page. That means it’s usually a video. You want that video to be compelling, but I’m not sure I’d use the word slick. What you want for people to come to your project and believe is that you’re capable of doing it and it’s going to deliver on what you’re promising. If you come in super slick but there isn’t a believable personality behind this, then I’m not sure that necessarily serves you well. Part of what people are looking at is, who are the people behind this project and do I believe they can actually do what they’re saying they can do.

Scott Steinberg: You have to double down on presentation. I don’t care what your budget is, one place you don’t cut is in terms of production value in that presentation. Keep in mind that people are very visual creatures and we tend to accept what we see. Most people are going to assign a worth to your project and a perceived value based on what they interpret from the video or the screen shots. You don’t go into the store looking for the crappy looking game. If you’re going to ask them to dip into their wallets, you need to have something very powerful to show. At the same time you need to tell a compelling story. Perhaps the most effective one I’ve ever seen is not a game. Amanda Palmer, who used to be on a major label, recently did a video for her book, CD and tour. She was asking for $100,000 and raised roughly over $700,000. In her video she appears holding a series of poster boards. She doesn’t speak a single word, effectively tells her story strictly through text. By the end of the video not only have you fallen in love with her, but you’ve fallen in love with the idea of what she’s trying to do. She shows very little actual material. You don’t hear a great deal of the soundtrack that she’s trying to add to the album, but really what you’re buying into is her creative vision.

Also sounds like she took a page out of Dylan, which I’m sure helped. You mentioned rewards and their importance. Is there a right formula or percentage of funding to put towards rewards for backers?

Jon Kimmich: The main thing to keep in mind is what are these rewards are actually going to cost you in terms of fulfillment and in terms of time and how much it takes away from your project. It’s the little things, like the cost of international shipping. Again, doing your homework on what your rewards are going to cost is important. And give yourself a certain amount of flexibility for doing crazy stuff, things that people haven’t done before. Some of them are going to work, some of them are not going to work, and that’s okay. If things aren’t working, you can adjust your campaign.

Scott Steinberg: The rewards are going to be ultimately designed around the type of project you’re offering and what materials are possible and what opportunities and what merchandise you have access to. What you want to do is offer a variety of compelling rewards, and it’s important to keep in mind that every single pricing tier should offer value. It’s not a charity fundraiser. You have to offer something of value in exchange for the pledge. At the same time it’s important to have variety that’s fairly evenly spaced out at all levels, starting at impulse buy and moving on up to special one-of-a-kind opportunities that are offered at a high price point. As Jon pointed out, throughout the campaign you’ll have to monitor which best connect with fans. Actually backers will oftentimes tell you which rewards they prefer. With Brian Fargo and Wasteland 2, the rewards they most expected to monetize were actually not selling that well, and so they went back and revisited them to add new bonuses, add new incentives, or add new rewards at different points of the campaign to find what clicked. It was iterative.

Let’s talk about marketing a finished project. Is that something a developer should be thinking about even as they’re trying to get their game crowd funded?

Jon Kimmich: Keep in mind the people that pledged for your product are in all likelihood going to be your most loyal supporters when it comes time to sell the product more broadly. Part of being successful is maintaining your existing relationship with those backers, and doing it past the point when the product launches.

Scott Steinberg: The consumers who are backers are brand evangelists already. That’s the beauty of crowd funding, it’s that from day not only are you generating awareness and doing promotional activity, you’re actually actively engaging fans and getting them emotionally connected to the project and its eventual outcome. Most of the activity is going to be at the social and grassroots level to make people aware that the product exists. At the same time it also has to be coupled with considerable PR activity, because what happens once the media covers it, they’ll be on to the next big product or project and consider it yesterday’s news. If you’re not shipping until eight months after you’ve raised awareness for your campaign, then you need to undertake activities designed in educating consumers that the product is indeed now available. As far as paid advertising solutions, it may be acquisition-led campaigns that are more effective. Even offering community members affiliate marketing, offering incentive that if you tell your friends about this we’ll give them a free weekend to play it, or we’ll give you ten bucks if they buy in. Because these products already have awareness and advocacy, really what you’re trying to do is tell consumers that they’re available. And a lot of it is an effort to create a sense of prestige around the product as well. Because effectively what you’re saying is that, in most cases creators build projects, they announce it and they hope it finds an audience. In this case, it’s the public who said you’re damn skippy we want this thing, so having a game by gamers for gamers can add cache and get people excited about it.

Jon Kimmich: I’ve occasionally heard folks say I’ve found all these backers for my campaign so I’m not going to do any more marketing on my product. I’ll just rely on them. I don’t think that’s necessarily an accurate view either.

Scott Steinberg: You absolutely have to do PR and marketing. You just have to be selective about your opportunities. What you’re not trying to do at that point is necessarily go broad and generate awareness. Really it’s an education and activation effort.

What do you think the future holds for crowd funding for games?

Scott Steinberg: We’re already hearing stories of fatigue because so many great opportunities have been launched back to back to back to back. There’s some attrition there in that, hey look, just because I contributed to one campaign doesn’t mean I want to hear about 15 of them by next Tuesday. Now what’s the maximum limit for that, when do we hit that point of saturation. It’s hard to say because what is technically being done here is, once upon a time you wanted to ship a game you had to go to a small group of very wealthy, influential individuals who decide what the masses want. In this case you’re flipping it out on its head and letting the masses decide what they want for themselves, which doesn’t necessarily align with corporate America’s vision. Crowd funding isn’t going to be right for all types of products or projects. What it is going to do is give birth to thousands of new games and ideas. I really think that people don’t grasp just how big the movement is going to become.

Jon Kimmich: If you look at the world of traditional games publishing, I’m not sure if this is necessarily going to have a huge impact on big budget triple-A console games any time soon. If you added up all of the money that’s been spent on crowd funded games across every crowd funding site in history to-date, it probably still wouldn’t add up to the amount it took to build one Halo or one Call of Duty. But if you’re a publisher who focuses more on digital distribution or smaller titles or indie games, then this can have a very material impact on your business.

Follow the authors for more tidbits from “The Crowdfunding Bible”:

Scott Steinberg

Twitter: @gadgetexpert

Jon Kimmich

Twitter: @jonkimmich