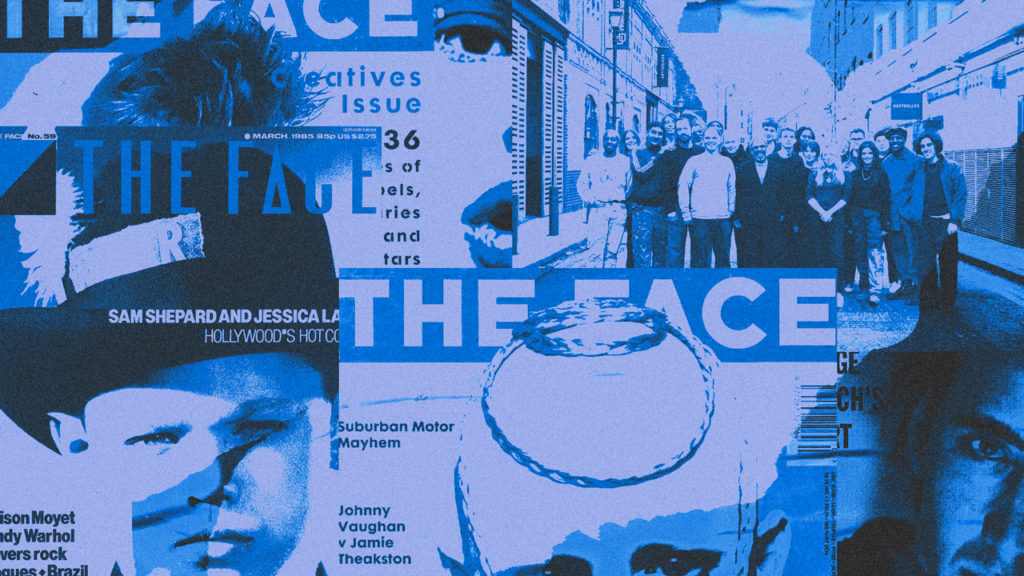

Jason Gonzalves is one of the brave bunch who decided to revive an iconic brand. He is responsible for the comeback of The Face,

“It’s always really lovely when you hear [personal stories about The Face], the warmth and affection from people who remember it. And people who weren’t really old enough to remember it the first time around, but have found old copies or archives. Just touching,” Gonzalves said about the magazine’s recent renaissance.

He also chatted with AList about other things, like the phenomenon of “the feed culture,” the difficulties of repositioning a brand, his decision to leave an agency career and more.

How did you make a decision to leave the agency you built to recreate The Face?

The truth is, I ended up at an advertising agency because I couldn’t get a job at The Face. I was a graduate who decided to please my Asian parents. I got [a] science [degree] when I wanted to be a fashion journalist and write for The Face. I came out of university with a degree in quantum physics and realized I was never going to be a scientist. I wanted to do something creative. And I was like, “All right, I’m going to end up in the agency world.” Weirdly, the fact that advertising was always my second choice, it was a really brilliant driving force for my career. I never wanted to make ads. I wanted to make things that were about culture. I brought that mindset to my career in advertising, It was a deep sense that I was going to try and do the closest thing that I could do to achieve my dream, and do it in the world of advertising. And that has been a big part of why I’ve been able to do so much [effective work] over the years. In truth, it’s like my destiny fulfilled.

I was the chief strategy officer and led BBH for 10 years. I tried to see if it was possible for BBH to buy The Face. My partner now, Dan Flower, [and I] looked to see if we could buy The Face through BBH because I feel like advertising needs to earn its right to take people’s attention. So many agencies say, “We create culture.” But they don’t, really. If you could take a publishing spirit and have a really strategic point of view about marketing, that is something really powerful.

When I heard that Wasted Talent bought The Face, I went back to that plan and said to [Wasted Talent CEO] Jerry [Perkins], “Look. I think I’ve got a good idea about how a publisher needs to operate right now, how it needs to show up in the digital world and how to make money out of it. And I’ve got [the] strong point of view about how The Face needs to work and I’d like to come and do that for you.” It was middle-aged wish fulfillment. It was a creative person’s dream come true for me. But also, I feel like I’ve developed this point of view about where the world is going, what audiences want and what probably advertisers want.

One of my clients for many years was The Guardian newspaper. I think what The Guardian‘s doing, and what The New York Times is doing in the world of news, is so important right now. I feel some of that zeal, that sense of purpose, should be brought to the areas of style, culture and music journalism. Some of that sense of purpose and the role that those things have in culture can be a galvanizing force in the world. That’s especially true for a generation of young people who are hugely motivated, critically creative, questioning, socially aware, politically active, but also want to party, want to look great, want to discover new types of culture—those things aren’t mutually exclusive. I think there’s a really exciting place to bring some of that sense of purpose and mission to the world of style and culture.

What are the beginning efforts of bringing the magazine back to life? How did you decide that you were going to use the old logo?

The big question that me and Dan Flower, the managing director, talked about before a single person was spoken to was, “Why does it need to exist? Why should it come back?” We have a lot of affection for it. I grew up [with] my eyes opened to a world of creativity through The Face, but [that was in the ’80s]. There were hardly any magazines on the newspaper rack. The newspapers really didn’t cover culture in the way they do now. There was very little in the way of television, certainly no internet.

We also spent a lot of time asking ourselves, “Does this need to exist and why?” And for us, [we feel culture] has become absolutely and utterly dominated by what we call “the feed culture.” The Facebook algorithm, the [chronology]. The whole way the social web works, you have to feed it, you have to keep giving it to people. And [when you think about audiences] you think about traffic through the feed.

What I think that means [is] that you’ve got a group over here who are all white, a group over here who are liberals, you’ve got a group over here interested in fashion, and [none of those little bubbles communicate with each other]. We thought, “That’s really interesting, but it feels like at a human level that’s not what people really want.” And The Face was always something that was incredibly multifaceted. It would talk about music, it would talk about entertainment, about sports, it would talk about political issues. And we thought, “Wow! That’s really exciting.”

In 1980, when it launched, Britain was in really fucked up place It had [a terrible economic meltdown in 1976]. There where worker strikes. There was rioting. There was racial tension. There was a government that was trying to destroy society, and [culture] is something that connects all of these themes and expresses it through music and attitude, look and identity. And that’s called style. Not style as a “this is what you wear” and “this is what you buy,” which is what it has become. Style is about attitude. I want a magazine that does that and that’s what The Face is doing. We just felt [that] almost 40 years later [it was] so much a mirror image of that time. We want to tap into some of that spirit, that sense of purpose and start a new conversation around style. A conversation around style that is positive and not just about consumption, it’s about how you express yourself. It is about identity. It’s about belonging. It is about unity.

And then we thought that if we could deliver it in a way that felt like it tapped into human needs, if there was a real sense of purpose there, that could galvanize it. What we also think is missing is a commitment to journalism in a contemporary way, asking the questions that matter. There is also a sense of positivity that is missing right now.

Also, repositioning a brand is like archaeology. You’re finding things, fragments, hidden in the history and heritage of the brand, uncovering them, dusting them off. And then you find a way to combine them in a completely new and fresh way. And to put them together but do that in a way that doesn’t just hark back to the past, but is a springboard to something new. And that’s what we wanted to do. Take the foundation and use all the things that weren’t available to the amazing journalists who were at The Face [at the time] to create a new expression of the original spirt. Today’s version is more dynamic with more voices, using video and engaging with the audience in interactive ways.

We liked the idea of keeping the masthead. We just felt like it was an incredibly simple, striking and iconic foundation. We wanted to respect the past in our fonts We wanted to pay a nod of respect to the foundations that were laid by the people who’d come before us. Incredible people, like Nick Logan, the founding editor, and Sheryl Garratt, probably the best editor that The Face ever had. Incredible designers, like Neville Brody and so many brilliant journalists and image-makers.

We owe a huge debt of gratitude to them but every one of those people would have said to us, “Don’t go back. Go forward.” Interestingly, one of the toughest things to think about, in terms of design refresh, was use of the typography. Because what Neville did was so iconic. What we designed was a nod to that. It was our way to take it forward.

We thought long and hard about how we’d do that. Who could we hire, who’s the new Neville Brody? The person we are most excited about working with in the world was Mirko Borsche, who runs a design studio called Bureau Borsche in Munich. We like his craft ethics, the range of his work, his point of view, culture and his punk ethic. And we started working with him.

You have a quantum physics degree so you’re at least a little bit analytical. How did you organize the relaunch on paper?

There were lots of moments where we thought we can’t write anything down. The old guard wouldn’t have written anything down. We wanted it to arrive organically. [Part of the evolution] was to keep questioning. Always asking not just what’s cool or what’s interesting, [but why has it got style]? Why does it matter? We are joining the dots between all the different parts of culture. Overall, it feels more like a movement than a magazine.

We were very focused on trying to get something out, and do it quickly. Basically, there was one person employed last year before Christmas and we went from that, to having a product that was out in the world in April. That involved hiring a team, staffing up, finding an office, building a website, designing, writing stories, philosophy, commercial deals and operations. We did all of that in about four months.

At advertising agencies, you spend so long planning that a lot of the magic is lost. And all that lightning in the bottle comes from that creative leap that happens in the moment. At agencies, the layers of process and approval and second-guessing a client who’s second-guessing their boss and all the rounds of approvals—that kills that magic. It’s rare that magic in a bottle gets any better over time. When you’ve got no time at all, that’s when amazing things happen. And when you’ve got people who operate in that way, it’s amazing.

Did you look at other publishers and what they were doing with brands and advertising? Have you been looking at that as you’ve been creating The Face‘s value proposition and partnering with brands?

We’ve looked at [ideas and strategies and actually spent many years at agencies looking at publishers and trying to understand what they’re doing well, and what they’re not]. One of the really fascinating learnings was seeing how the record industry fucked up. Which is business 101, isn’t it? An example of how not to drive off a cliff. The record industry got itself into trouble because it believed it was in the industry of making records. It believed it was a mass industrialized business, churning out pieces of vinyl. In reality, the high-value proposition was always about this magical relationship between artists and fans. The records happened to be one of the conduits, and so they were really focused on how they could commercialize an object. [It was a record and then it was a CD]. But the really high-value proposition was the incredible relationship. And in a way, publishing did that, too.

Publishing is the means, the medium, for creating a relationship between creative people and audiences. Both are connecting audiences to what’s happening in culture. And I think for me, that’s the proposition. What we do is create value in cultural relevance. Some of that comes through our own publishing and some of that we monetize through advertising. For us, that looks less like conventional ads and more about co-creating with brands. But right now, that’s what we’re about [having an incredible operation that understands cultural relevance], and then thinking about different ways to turn that into brand value. Over time we see ourselves developing our own products, our own life experiences and our own IP, and becoming a go-to production house for commissioning from the big platforms.

Do you think that the UK publishing is uniquely capable of sustaining a comeback of this sort?

Comebacks are always hard. One of our massive advantages is this incredible brand. For example, Alessandro Michele, the creative director at Gucci, called us up and said, “I want to do a collection and [I want to incorporate The Face into my collection].” His pre-fall ’19 collection has 20 pieces from The Face, using The Face logo in the collection. That’s because of the strength of the brand. It’s so powerful even after 16 years of being away that people like Michele want to have the Gucci brand associated with it.

But the brand has no legacy infrastructure. [It] hasn’t existed for 16 years. So we don’t have all the problems of transforming an infrastructure and all the pain that comes with that. We can take this incredible brand, and with a completely blank piece of paper, build a business that’s right, right now. That is a unique opportunity. If you can do that and there are people who want to be part of it, that [speaks to the fact] that some of these incredible magazines are just incredible culture brands.

More than ever young people especially look at brands like that as an extension of themselves as well.

That’s an incredibly smart thing to say. They think about brands in an incredibly fluid way. It’s a generational thing to think about brands like that. It’s actually a very postmodern thought that a brand isn’t really just a descriptor of a product. It is actually about [an idea, a set of ideas or a set of values]. It’s a point of view of the world. How that is expressed can be quite fluid. I think the audience is very comfortable with that. I’ve heard a few [old school publishers] going, “Oh, e-comm. That feels like you’re de-valuing the editorial.” I think that’s quite an old-fashioned way of thinking about it. A brand that is about culture and thinks about how to create something interesting in the retail space is a different form of storytelling.

A lot of the really interesting publishers right now are actually e-comm businesses, for example, Farfetch. They’re basically an e-comm platform but they really [are] publishers. As long as you approach these things with integrity and a point of view rather than thinking about it as a platform (which is really only about the technology and scaling), then I think you can succeed. Of course, you have to scale, but you have to have integrity [while doing it]. You’ve got to have value. You’ve got to have a product and you need to create a voice. It’s an incredibly exciting time.