By Meelad Sadat

VentureBeat ventured into game industry coverage with little fanfare. It didn’t lure away an army of well-known editors from game sites. It didn’t promise to revolutionize game press. It didn’t unleash a slick branding campaign. It launched as a one man show, hiring veteran games business writer and author, Dean Takahashi. So subdued was the effort that as Takahashi puts it, he wasn’t even sure games were going to be his beat.

“When I joined VentureBeat four years ago I thought I was going to stop covering games because there was no such thing as a venture capitalist investing in games,” says Takahashi.

But he adds that, to his surprise, things drastically changed during his time at the site. Games are now considered serious endeavors with big upside potential for VC and angel investors. Facebook and Zynga have helped. So have the slew of startup successes feeding off of the growth of digital distribution.

During the same period of time, VentureBeat’s foray into games became a success story in itself. Today, the site’s GamesBeat section is a fully-staffed, well-read media outlet covering games from both business and product standpoints, including offering up comprehensive game reviews. Over the past year it’s added game press talent to its roster, with Dan Hsu, Sebastian Haley, and a staff of hardcore gaming freelancers from Hsu’s crowd sourcing site Bitmob. GamesBeat is also now the organizer of an eponymous annual conference gathering game industry heavyweights.

With GamesBeat 2012 {link no longer active} on the horizon in early July, we talked with Takahashi about their growth, and about his views on drastic changes in the industry and even the changing face of E3 in the four years since the site launched.

[a]list: Tell me a little bit about the growth of GamesBeat over the past few years.

Dean Takahashi: Venture Beat has been tripling its traffic every year. We finally got big enough in the past year or so to take on GamesBeat as a real, second site and a new project. That has grown dramatically for us. We expanded by bringing Sebastian Haley as our review editor back in October, and Dan Hsu started earlier this year for us. They brought with them a lot of freelance writers from the crowd source site that we acquired, Bitmob, which Hsu was running. That’s given us a very large writing staff for covering games. At E3, we had nine writers and editors this year. A year ago, this time, we had three writers at E3.

[a]list: GamesBeat has become a bigger and bigger part of a site that’s geared towards the venture capital community. Does that success you’ve had with readership reflect growing interest in the game industry among VCs over the same period of time

Dean Takahashi: Definitely. When I joined VentureBeat four years ago I thought I was going to stop covering games because there was no such thing as a venture capitalist investing in games. Not so long after that social gaming exploded on Facebook and the venture capital started flowing. Now we’ve got a couple of IPOs, and a couple billion dollars on top of that invested into more than a hundred game startups. That sort of came out of nowhere the past four years, surprised everybody, surprised me. Clearly games have turned into one of the great investments in the last few years, alongside things like Facebook and Apple. The growth of apps, the disruption that has resulted for traditional games because of social, mobile and online is really fueling the growth. We’ve tried to cover that disruption or that change a lot more closely than other publications.

[a]list: Let’s talk about your upcoming GamesBeat conference. You’re in your fourth year, and that’s arguably the most transformative four years in the history of games. Looking at your conferences year over year, how would you sum up the major changes and trends over that period of time?

Dean Takahashi: We’ve found a big crowd who’s interested in the cutting edge of games. That’s where we target all of the speakers and the panels. We had Mark Pincus from Zynga on one of our panels at the 2009 conference, and he’s coming back as a multi-billionaire as a fireside speaker at this conference. Last year we focused on mobile games in particular because there was this theory that Zynga was dominating Facebook and so the wide open territory for startups to invest in was mobile. A lot of those happened.

Now we have this theme for this year’s conference that it’s the cross-over era, where the different barriers that have held up over the years between the different segments of the game industry are all coming down. The web itself has obliterated them, and there’s a lot of movement back and forth between console, social and online now. This year’s conference has a lot of speakers from big game companies, the traditional ones, as well as the disruptive startups. We always try to focus the conversation on what’s on the cutting edge and what’s disruptive.

[a]list: One of the areas that could be somewhat disruptive is this growing idea that there’s a market for core games on mobile or tablets, and that there’s going to be this category called mid-core with games that look like console games to an extent but are designed specifically for mobile platforms. Do you think this is a significant opportunity and is it right for developers to target it?

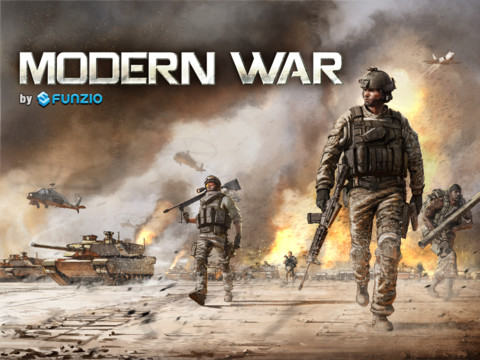

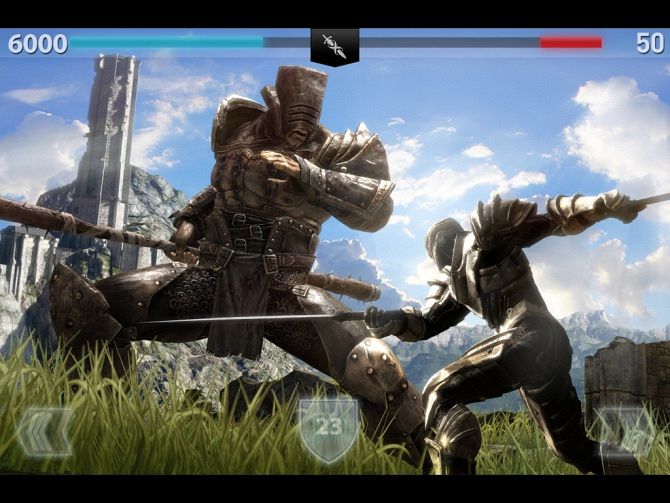

Dean Takahashi: I think there are definitely some great examples of success on that front. Funzio had pretty good success with a string of games. They went three for three above a million users on iOS. Kabam has had great success with Kingdoms of Camelot: Battle for the North. There are other hardcore games out there like Infinity Blade from Epic and ChAIR Entertainment. Those games are proving that hardcore gamers are on the platform and they want to play games. As you said, mid-core is sort of like a ratcheted down experience because it is a different type of platform where you play for a shorter amount of time. So those kinds of games are making sense for sure. I think we’re just at the beginning of this.

[a]list: If you were to define the kind of core gamers that are playing these games on mobile, who is it, is it gamers filling up their time away from consoles or is there an actual migration happening?

Dean Takahashi: I think it’s everybody because these games and other free-to-play games can reach a much wider net and a wider audience because that barrier isn’t there where you have to pay sixty bucks for this game. That creates a very large funnel for the game companies that are grabbing just anybody they can, and then it narrows down based on who’s willing to pay for something like virtual goods in a game through micro-transactions. That becomes more the core group of fans gathered around different titles. It’s an interesting blend because those hardcore players wouldn’t be there if the game wasn’t populated, if there weren’t many players in it. The large majority of players aren’t monetized there but they provide a valuable function by making the game feel very popular and populated.

[a]list: What are your views on the sudden growth of Kickstarter and crowd-funded projects in the game industry, is it a threat to traditional investing?

Dean Takahashi: It’s a much needed breath of fresh air for funding games in the middle layer of gaming. The blockbuster games get all of the funding they need from major publishers. The small indie games don’t take much money, and so a group of just a few people can work on them and get something to market. But this middle layer of publishers and developers who didn’t have gigantic hits but have games that deserve sequels or properties in need of a reboot, those are the ones cashing in pretty big on Kickstarter. The big thing about Kickstarter is that it comes from the fans, and the fans can validate the idea of doing a game. Like the revival of Wasteland that Brian Fargo is doing. He got a lot of money, nearly a million bucks out of that. He also sort of validated that a lot of fans still care about the franchise. I think there’s still a need for venture funding for companies that are more ambitious, that want to raise more money, like five million bucks and upward. It’s pretty hard to imagine that crowd-funding sources are going to produce that much money. This middle layer of people who are well known already as developers, who have some property that they can revive, are the ones that I think are going to benefit most from Kickstarter.

[a]list: Has there been any rumbling among the VC community about how they feel about crowd-sourcing?

Dean Takahashi: I think they sort of realize that they have to bring their own value to the equation, that they can’t get as greedy as they might be in the absence of Kickstarter. It kind of keeps everybody honest. The VCs can’t take a controlling stake in a company for a very small amount of money. There’s a checks and balances system here. If the deal you’re getting from a VC or angels is an ownership one, you have an alternative now to go shopping for money on Kickstarter without giving up any equity.

[a]list: Let’s get your thoughts on E3. There’s this question of the viability of E3, now that there seems to be fewer major announcements made at the show. There’s also the question of where it should be located, whether it should stay in Los Angeles. What are you views

Dean Takahashi: First, I think it should stay in LA. It’s the center of entertainment in the country. It makes sense to have all of the entertainment industry represented at the show. If they move it out, maybe they move it out for a couple of years then come back to LA at some point, just because of the construction issues really. [Editor’s note: LA is mulling a new football stadium.] They could try to put it in other big cities like Las Vegas, but there are a lot of pluses and minuses there, with too many distractions in Las Vegas.

The Last of Us

The Last of Us

As far as the show itself, I disagree with people who think it’s over. I think it’s still a very valuable venue and it’s going to be so for a long time, especially for a lot of the major tent pole announcements of the game industry. This was an in-between year so it’s sort of unfair to criticize it and say there was nothing that exciting at E3. Nintendo’s console announcement could have been better. By next year we’ll have some new console announcements coming from Microsoft and from Sony that will sort of put some life back into E3. I think there were really some good surprises in the games that were shown by different players. Sony scored very well with brand new intellectual property with games like Beyond: Two Souls, The Last of Us and The Unfinished Swan. Ubisoft also had a very good showing with some very solid sequel games like Assassin’s Creed 3 and Far Cry 3. They also had a brand new title in Watch Dogs that wowed the audience at their press conference. If you add all of that up, it wasn’t that disappointing. I think Microsoft and Nintendo could have shown their games better. They looked weaker by comparison.

[a]list: With Nintendo, where do you think they came up short in the way they showed the Wii U?

Dean Takahashi: They have a major issue with the capability of the Wii U console where it has a single processor but it has to drive multiple displays. A single graphics chip inside the console has to drive the big screen, the main game screen, but it also has to provide the imagery for the tablet controller, the game pad. And yet the system itself isn’t that powerful. Nintendo only showed games with one game pad controller and the TV. Most games out there, if you’re in a social setting, you want two controllers. Nintendo didn’t show any games that do that. They admitted in a Q&A that the games are going to run slower if you have two game pads and playing on a main display. That’s a fairly big issue for them. They made a good case that you can play with one controller and multiple Wii controllers, what they call asymmetric gaming where one person is looking at the small tablet screen and trying to deploy zombies while the people playing with the controllers were all on the main screen. You come up with very creative, different kinds of games where it’s one against four, or one person going online. They tried to justify and turn into an advantage this major weakness of the Wii U, but I think a lot of people saw this as a weakness. The games themselves were creative. They tried to do something like Wii Sports with NintendoLand, which has mini-games in it that explore the capabilities of the tablet and the touch screen. But there wasn’t an obvious blockbuster within those games. They may have had a good one in ZombieU, but in the demos it didn’t necessarily play that well. Nintendo came up as a pretty big disappointment at E3.

[a]list: I know you’re a gamer. What are you playing and what are you most looking forward to?

Dean Takahashi: I just finished playing Max Payne 3. I think I’ve slayed more than 1,500 people one at a time. It’s interesting for that game, which is a very cinematic game with some outstanding cut scenes and a character driven story. Yet at E3 some of the most interesting games to me like Tomb Raider, The Last of Us and Beyond: Two Souls, they had confrontations in them with a lot fewer people. A lot fewer people to shoot but each conflict was a life and death struggle with someone who was just about as capable as you were. Instead of shooting a hundred people, it seemed you might kill one or two, and also in a more brutal way. These games that are coming up that I mentioned are much more emotionally rooted, almost like movies in the impact they can make and the power of these scenes. They can sort of make Max Payne 3 seem like kid’s stuff by comparison. The only worry that I have is they might seem too scripted to the gamer, where you’re not controlling the game as hands-on as you would like, and that it’s more like watching a movie unfold in front of you. The game industry has gone down that road and made that mistake before. It’s a hard problem to solve in how much can you increase the drama of a game before it’s no longer a game and turns into a movie.

[a]list: Thanks, Dean.

Peter Della Penna

Peter Della Penna

Greg Agius

Greg Agius

Jonas Antonsson

Jonas Antonsson Dark M&Ms Ad

Dark M&Ms Ad Vikings of Thule

Vikings of Thule